This weekend, Members of the Epping Forest and Commons Committee headed to north-east Surrey for a site visit to Ashtead Common.

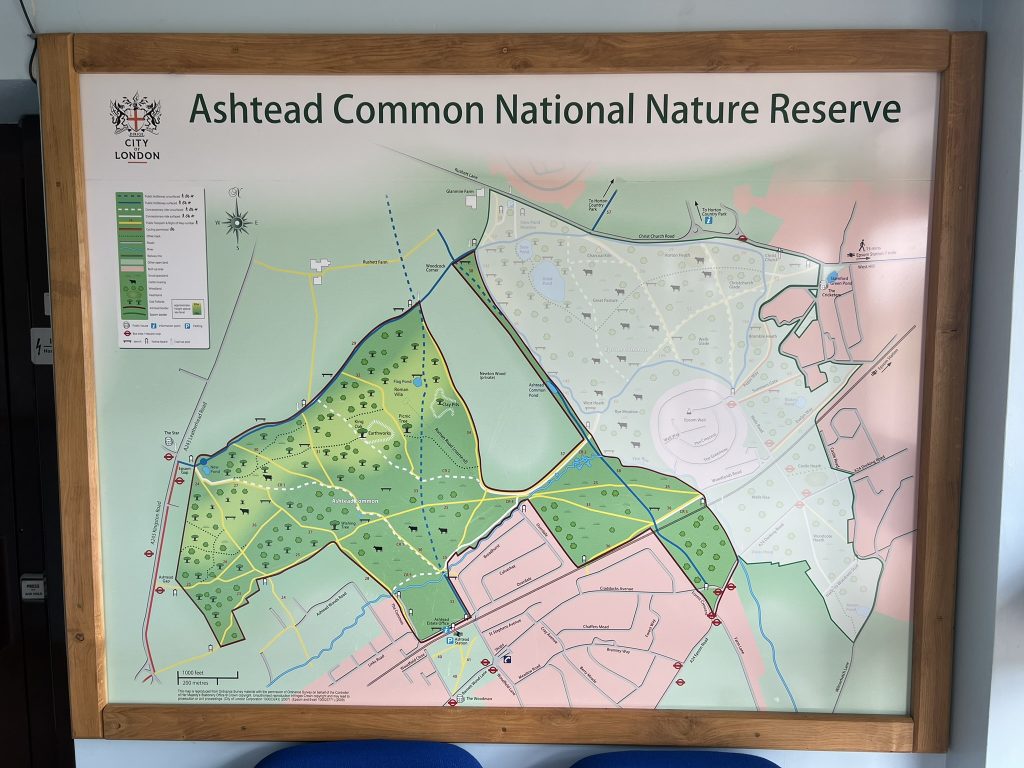

The 450 acre Common is designated as National Nature Reserve – home to over 1,000 ancient oak pollards and a mix of rare wildlife. Together, with Epsom Common, it was also designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 1955 for its diversity of habitat, rare invertebrates (particularly decaying wood specialists, flies and butterflies) and rich community of breeding birds. The pollarded veteran trees make an impressive home for animals and fungi in decaying wood, but it also has a mix of bracken, scrub grassland, semi-improved neutral grassland and various aquatic habitats.

Like many of the green spaces conserved by the City of London Corporation for public recreation, Ashtead Common is open all year round and is easily accessed by public transport. I recently came across a Transport for London poster from 1921 promoting Ashtead. Indeed, this was one in a series of promoting cheap, sustainable transport options to open spaces like Epping Forest.

We began our visit with a discussion about public access restrictions on Woodfield to support the conservation of skylarks, as ground-nesting birds which are rapidly disappearing around London. The fencing helps keep dogs and other animals out of the nesting site between February and September. It’s great to hear local people have been so supportive of this conservation initiative. Hearing the song of a skylark is a pretty impressive experience, which we would love the next generation to enjoy too.

We then moved on to discuss some water quality monitoring we have installed at Ashtead. The water system has inflows from the Rye Brook and the output is now showing that the quality is four times worse than slightly further upstream. This is predominantly due to pollution from road surface water run-off and some unlicensed sewage discharge. Monitoring the data allows us the evidence base to make representations to the Environment Agency, where necessary.

Our team are in the very early stages of working with consultants to draw up plans to create a new wetland area, where a reed bed filtration system could help improve the water quality of the Rye Brook.

Another project our team are working on is the creation of ‘leaky wood dams’. These are designed to slow the movement of water after high rainfall and help push water onto floodplains. They can also increase the recharge of groundwater, which increases the temporary storage of flood waters within water channels and on floodplains. The benefits are that they delay the passage of floor water downstream, allow sediment to settle out and reduce flood risk.

During the winter months, Ashtead’s bridleways and permissive path network can become extremely wet and muddy, so work has begun to install 14 new leaky dams across the site. This is funded through the City of London Corporation’s Climate Action Strategy.

Volunteers make an enormous contribution to conservation management at Ashtead. Many of the cyclical works are performed alongside volunteers groups – made up of a mix of local residents and corporate.

A new group has recently been established to reach out to young people through the Duke of Edinburgh’s Gold and Silver award volunteering programs, to attract the next generation to help take care of this site in the future.

Ancient tree pollarding is clearly an important task at Ashtead. The team have been updating the ancient tree work program ahead of the City of London Corporation hosting the UK Ancient Tree Conference in June this year.

The team are exploring techniques to ‘veteranize’ younger trees to provide some of the habitat ancient tree provide to help improve biodiversity at Ashsted. The team have been working with a researcher from Sweden on this. They have also been partnering with Natural England and Cardiff University on a further project involving inoculating fungi into trees.

In 2017, the City of London Corporation commissioned Surrey Wildlife Trust to graze parts of Ashtead Common on our behalf. Over the past year, there has been a significant expansion of grazing to 100% of the site, now using NoFence GPS collars to manage the herd.

The Belted Galloway cattle are a hardy breed which are well-suited to life on the Common. They do an excellent job in clearing much of the bracken, brambles and scrub, leaving behind a nutrient rich manure which sustains many protected insects species and feeds the earth below.

The cattle are not the only recycling team hard at work in Ashtead Common. It was great to see the scale of recycling natural materials, where fence posts, gates, notice boards and many other objects are made from materials grown at Ashtead Common.

Planning pressures have increased the number of visitors which frequent the City Corporation’s open spaces across London and the South East of England. At Ashtead Common, a range of different techniques are being used to protect the roots of ancient trees, in an attempt to avoid soil compaction and root damage.

This has included changes to paths and changes to maintenance around the trunks of trees. Brambles have been allowed to grow around the base of ancient trees which can benefit from less footfall over their roots.

Finally, we visited Ashtead Common’s Roman Villa and Tile Works, which is a scheduled monument with Historic England.

The monument includes a minor Roman villa surviving as buried remains. The villa was approached by a branch of the Roman road known as Stane Street. The stone walls and foundations survive below-ground preserving much of the original ground plan of the villa. It is laid out on a corridor plan with a series of rooms set behind a corridor running the length of the building. It includes a bath annexe to the rear. Several of the rooms were heated by a hypocaust and include the remains of pilae, flue tiles and adjoining furnace pits. The floors are partly paved with brick but the remains of tesserae indicate that at least some of the rooms were originally tessellated. One room includes the remains of a hearth and an oven. The site was partially excavated in 1924-9, 1964-66 and 2006-7. The finds included Prehistoric pottery, Roman flue tiles with pattern and pictorial designs, Roman coarse-ware pottery, animal bones, oyster shells, a column made of segmental tiles, a coin, a bronze brooch and a gold pendant earring. The excavations indicated that the villa adjoined a large scale tile manufactory and uncovered the remains of a separate bath house to the south. The site was occupied from about the second half of the first century AD to the late second century AD. The first buildings are thought to have been erected from about AD 67. However in about AD 150 the buildings were dismantled and in AD180 the villa was partly rebuilt.

Further archaeological remains survive within the vicinity of this monument. Some such as a nearby undated earthwork are scheduled, but others are not because they have not been formally assessed. The tile manufactory includes a number of tile and brick kilns and quarries to the north-east of the villa. The detached bath house south of the villa includes a circular laconicum. The bath house may have been used by those working at the tile manufactory.

We have aspirations to further celebrate the historic story of the site, but the introduction of a new interpretation board starts to share the importance of the site with visitors. We are pleased to have Elizabeth Corrin recently join the Epping Forest and Commons Committee which oversees the management of Ashtead Common. Elizabeth previously worked in the Museum of London’s Archaeological Service and is a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

We are also pleased to see the replacement of aged public information notice boards around Ashtead Common. The Superintendent proudly displaying one of the new installations below.

A really useful visit and great to spend time chatting with the hard-working local team. My thanks to everyone involved in maintaining this wonderful asset to such a high standard.