Buckinghamshire is home to many important natural woodlands. One of those is Burnham Beeches, situated between Slough and Beaconsfield, which is owned, managed and conserved by the City of London Corporation. It has long been one of the places in South Buckinghamshire to visit, whether you live locally or travel there from further away.

Burnham Beeches, a national treasure – the area known as Burnham Beeches has a wide variety of landscapes including woodland, heathland, bog, grassland and wood pasture. It was common land owned by the Lord of the Manor of East Burnham and used by the commoners of the manor for grazing cattle, pigs, horses and sheep and to provide firewood for fuel. The Grenville family of Dropmore were Lords of the Manor from 1830 to 1879, when the estate was sold to the City of London Corporation. They have the duty to “protect and conserve Burnham Beeches for public recreation and wildlife conservation in perpetuity”.

In Victorian times many of the old trees were given names because of their distinctive shapes. ‘His Majesty’ was one of the largest, the ‘Elephant tree’ looked like an elephant on its back, the ‘Lace Maker’ was where the ladies sat to make lace and the ‘Maiden Tree’ was an old tree that had not been pollarded. At over 700 years old, Druids Oak is probably the oldest tree still alive in Burnham Beeches.

The Beeches has always been a popular place for family walks, picnics and Sunday school outings but after 1880 it became especially so for visitors from London. They would catch a train to Slough, from where a bus service ran from the station which stopped at Wingrove’s tea rooms on the south-western boundary of the site.

The Edwardian years early in the 20th century saw proponents of the developing hobby of photography flocking to the Beeches to use the ancient trees as a background for their photographs. Exposure times were long in those days, and the structure of these trees provided an unusual but relatively comfortable place for participants to remain still.

Cycling was another up-and coming hobby, with the Beeches a popular place to visit. Later the cyclist would be joined by motor cyclists.

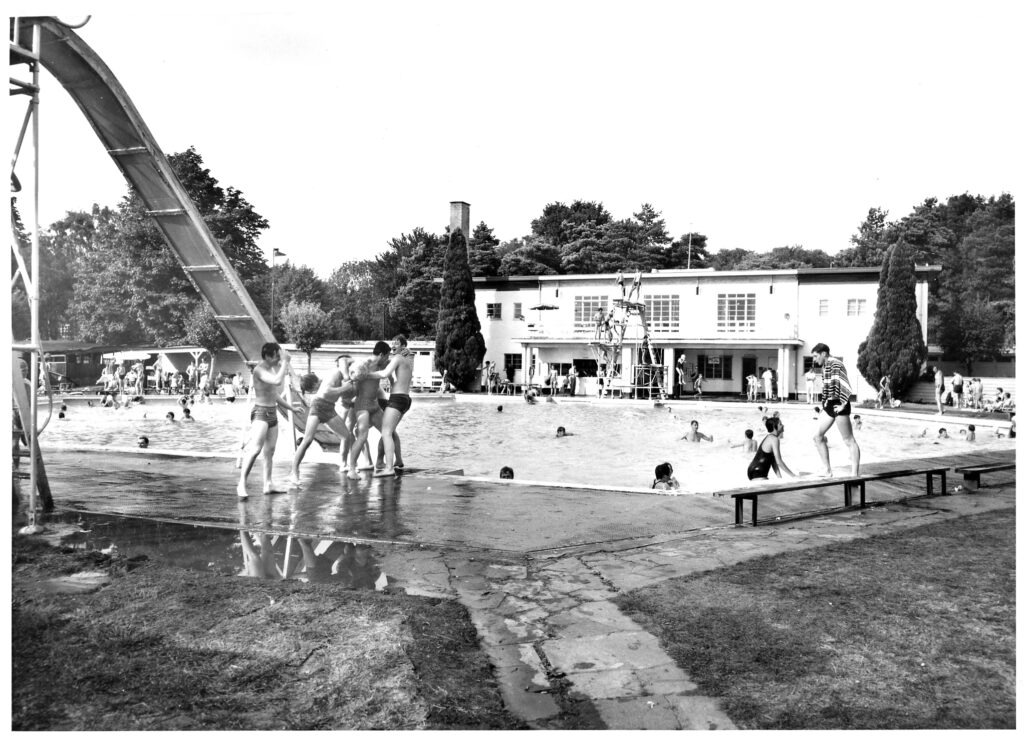

A major event which took place in 1934, saw an early version of the leisure centre constructed on the periphery of the Beeches, in Hawthorne Lane, Farnham Common. This included an outdoor swimming pool which was formally opened on July 28, 1934.

Burnham Beeches in WW2 This part of the article has been contributed by Chris Morris, who is Senior Ranger, Burnham Beeches & Stoke Common.

Although you may think Burnham Beeches is a natural woodland, the way it looks today is the result of continuous human activity over thousands of years, but arguably the most significant (albeit relatively temporary) change took place over a relatively short period of time. This was when the Beeches was requisitioned by the War Department in May 1942, to be used as a military camp for storing military vehicles in the preparations for the allied invasion of Europe. The woodland was encircled with barbed wire and became known as Vehicle Reserve Depot 2; its function was to receive wheeled vehicles, repair them, kit them out and hide them under the trees, out of the view of enemy bombers. The Beeches became one of the most important sites in the country in the preparations for Operation Overlord, D-Day.

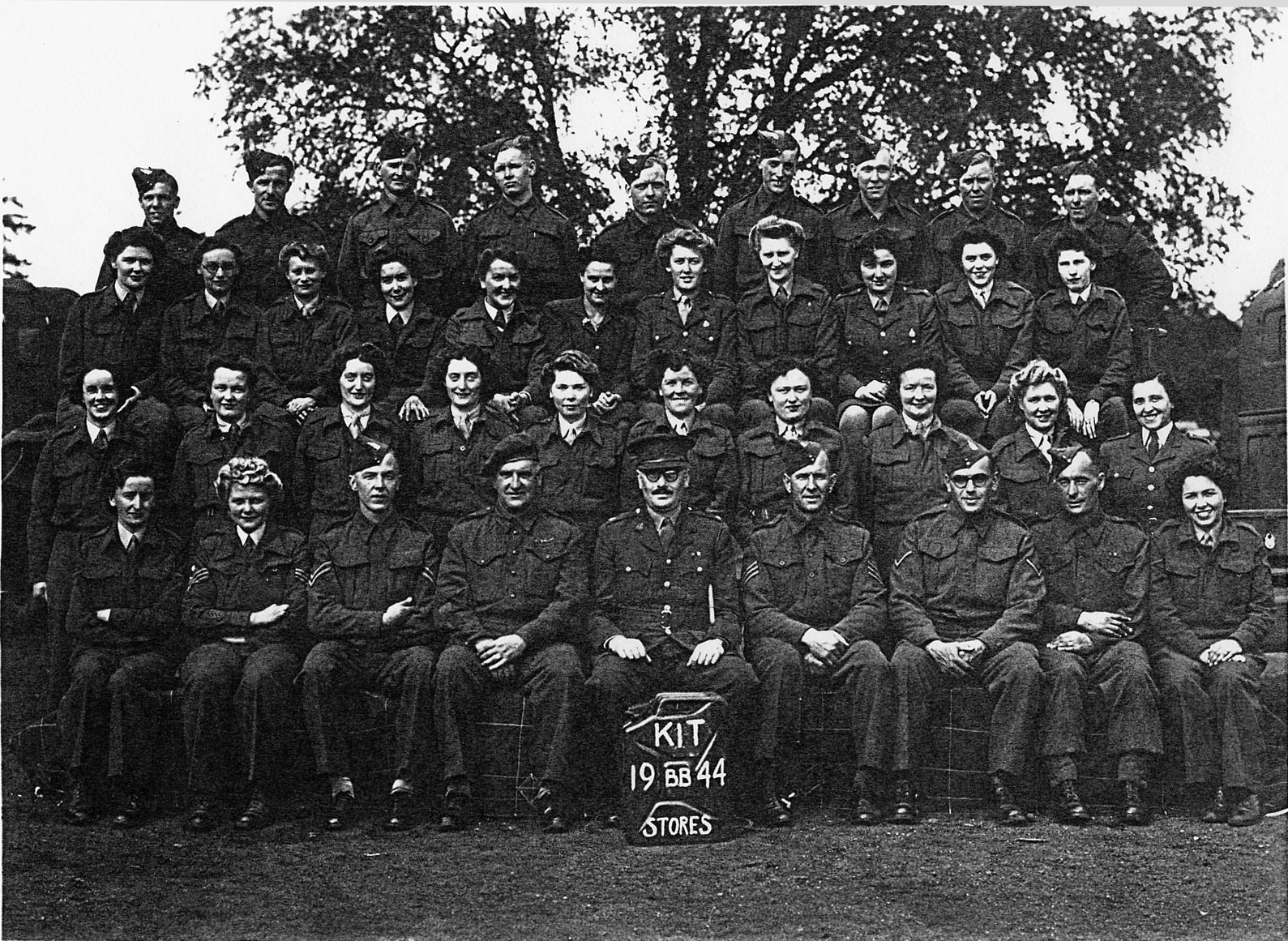

The base was administered by the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) and was transformed with all the buildings and equipment that you may expect of a regular army camp. This even included anti-aircraft gun emplacements and a prisoner of war camp near Stag Common. Over 300 personnel served in the Burnham Beeches camp including the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, the Royal Army Service Corps and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS – an all-female branch of the British Army). Male soldiers had accommodation in huts on the Iron Age Hillfort at Seven Ways Palin, whereas female soldiers were billeted in houses nearby.

To facilitate driving and parking the heavy military vehicles in the woods, around 275,000 tons of rubble (much from buildings bombed during the blitz) was deposited along paths. The camp needed electricity and a communication network, so many miles of power and telephone cables were installed, using the trees in place of telegraph poles to fix the porcelain insulators. Some of the rubble can still be seen along Burnham Walk and there are some insulators scattered across the nature reserve.

Vehicles entered the depot from Beeches Road (people who lived locally at the time have told us of big queues of military vehicles stretching to the A355) and were sorted depending upon their type and condition. They would then be parked in groups of vehicle-type, and have batteries, distributor caps and rotor arms removed, and antifreeze drained (a cracked engine block was a court martial offence). The trees provided perfect camouflage – so perfect in fact that on only one occasion did a parachute bomb find the reserve and then it fell harmlessly into woods without injury or damage caused. When the time came to send vehicles to the south coast, they left in huge convoys under the cover of darkness (mostly driven by the ATS) with drivers returning on lorries to repeat the process on subsequent nights. In total, it is believed that 100,000 vehicles passed through the ancient woodland.

It was not until 1946 that work started on removing some of the huts, but as many had been occupied by civilians displaced from bombed areas, full re-instatement was not complete until the early 1950’s.

Whilst we know that some trees were cut down by the army, some of the ancient archaeology was damaged in the construction of the camp, and you can still find the occasional clue sticking out of the ground or fixed to a tree, it is unclear what long-term impact the military activity may have had on the nature reserve. The good thing today is however that Burnham Beeches remains one of the most important places in Europe for some of the habitats and species found here.

‘The Commons’ Burnham Beeches is part of the network of areas collectively known as ‘The Commons’, which are owned, managed and conserved by the City of London Corporation. ‘The Commons’ comprises West Wickham Common and Spring Park (The West Wickham Commons); Farthing Downs, Coulsdon, Kenley, and Riddlesdown Commons (The Coulsdon Commons); Burnham Beeches and Stoke Common; and Ashtead Common. These are a valued collective of open spaces which include Sites of Special Scientific Interest, historic landscapes, Scheduled Monuments, and other nationally important features.

Together they cover an area of around 2,000 acres and make up over 18% of the 11,000 acres protected by the City Corporation across London and southeast England. Many of these spaces were purchased by the organisation to protect them from being lost to the urban development of the capital during the mid-nineteenth century, with the more recent acquisitions at Ashtead Common, Stoke Common, and Coulsdon Commons in the last 30 years. They attract around 1.6 million visitors per year.

The City Corporation’s green spaces help provide an important environmental halo around London and are a priceless sanctuary for many people. ‘The Commons’ play a critical role, as both a home to many rare species of flora and fauna and as a space for local communities to relax, enjoy and explore nature.